Adults often find surprising subtexts in children’s literature – but are they really there? Hephzibah Anderson delves into the world of Freud and fairy tales.

成年读者经常能在儿童读物中发现令人意想不到的潜台词——但这些潜台词真的存在吗?赫弗齐芭褠德森深入探究了弗洛伊德理论和童话世界。

——编者按

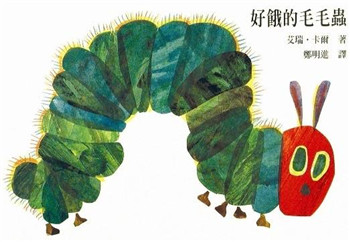

It’s easy to poke fun at some of these outlandish readings. Could they perhaps be the products of parents so addled by a text that, following their umpteenth nightly recital, the words start acting like one of those magic-eye images? Stare at them long enough and sense will materialise. Or nonsense. How else could a 22-page picture book like The Very Hungry Caterpillar yield capitalist, Christian, feminist, Marxist, queer and anti-liberal messages?

这些古怪的解读很容易被人嘲笑。它们可能只是床头故事而已——在儿时无数次的夜里,孩子在父母柔和的朗读声中展开魔幻的幻象。盯着这些幻象,越能感觉它们的实在。又或者,这是都是扯淡。难道说只有22页的画册《好饿的毛毛虫》能够包含所有资本主义者、基督教徒、女权主义、马克思主义者、同性恋者和反自由主义者的信息?

“I don’t think you can ever dig too deeply for meaning,” says Dr Alison Waller, Senior Lecturer at the University of Roehampton’s National Centre of Research for Children’s Literature. Her favourite class involves applying psychoanalytical theory to Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea, resulting in some decidedly Oedipal interpretations of that big cat and his relationship to the family.“

"我认为你不能太过于深挖儿童文学的深层含义。”艾莉森·沃特博士说道。她是罗汉普顿大学国家儿童文学研究中心的高级讲师。她最喜欢的课程是用心理分析理论来解读朱迪思·克尔的《老虎来喝下午茶》,并从老虎和它的家庭关系中得出了一些恋母情结的结论。