Q. Sakamaki has lived his life as an outsider.

Q. Sakamaki在生活中就是一个局外人。

As a Japanese photographer based in New York City since 1986, Mr. Sakamaki has spent nearly the last 30 years far from home, documenting wars, conflict and demonstrations. Even growing up in Japan, he moved from place to place, becoming an outsider in his native land.

他是一名日本摄影师,自1986年起常驻纽约,远离家乡30年。他拍摄过战争、冲突、游行示威。即使是在日本长大期间,他也曾多次搬离居住地点,成为家乡的局外人。

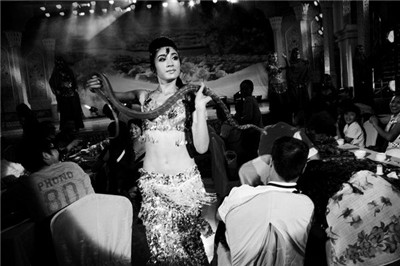

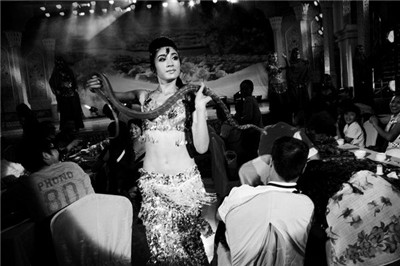

Now, Mr. Sakamaki has turned to China’s fringe provinces — Xinjian, Yunnan, Liaoning and others — where his project, “China’s Outer Lands,” catalogs marginalized minority groups that are rapidly becoming strangers in the territories they call home. The work is on display at The Half King in Manhattan until May 24.

现在,Sakamaki来到中国的新疆、云南、辽宁等边远省份,拍摄他的摄影项目“中国的边远地带”。这个项目纪录了中国边远地区的少数族群,正在迅速变为那片他们称之为故乡的土地的局外人。Sakamaki的作品正在曼哈顿The Half King展出,直至5月24日。

“ ‘China’s Outer Lands’ is about people instinctively looking for their own identity, between conformity or originality or autonomy or dependence,” Mr. Sakamaki said. “It’s natural, it’s happening in not only China, it’s everywhere.”This project is part of a larger, global story Mr. Sakamaki wants to tell. While “China’s Outer Lands” shows the clash between modernity and tradition in China, Mr. Sakamaki says that this conflict, along with wars and migration, has existed in other places and eras, such as during the campaigns of Genghis Khan.

“‘中国的边远地带’是关于人们在遵从和独创、自治与依赖之间,本能地寻找自己的身份认同,”Sakamaki说,“这是很自然的,不仅发生在中国,也发生在世界的每个地方。” 这个项目是Sakamaki想要讲述的一个更大的、全球性故事的一部分。Sakamaki说,“中国的边远地带”表现出中国的现代化与传统之间的冲突。这种冲突,随着战争和迁徙的发生,也存在在其他的地方和年代,例如在成吉思汗时代的战役。

“Behind the scenes, it’s not a romantic story,” he said. “It’s actually more like blood, blood, blood in history. One small change-up of power creates a huge wave of migration, often with new, bloody war. History shows that.”

“在镜头的背后,不是浪漫的故事,”他说,“实际上它更像是历史中的血腥、血腥、血腥。一次小型的权力交替都会制造出新的血腥战争以及大规模的移居潮。历史已经证明了这一点。”

Chinese development in Xinjiang Province has attracted a rush of Han migrant workers, and Mr. Sakamaki says the native Uighur population, which practices Islam, is being marginalized. The juxtaposition drawn between the Uighur inhabitants of the region and the migrant Han workers is stark.

Sakamaki说,中国新疆地区的发展吸引了一大批汉族打工者前来,而本土信奉伊斯兰教的维吾尔族人被边缘化了。这种维吾尔族居民与汉族打工者的并存很突兀。

A Han couple poses in a field, dressed in traditional Western wedding clothes, as newly installed wind turbines tower over the countryside. Other signs of China’s new industrialism dominate the landscape.

一对汉族夫妇身穿传统西式婚纱在田野间拍照,身后是新安装的风力涡轮机塔架。其他中国新工业化的标志占据了整幅风景。

But in the same province, the silhouette of a Uighur boy is shown as he looks at the rubble of a demolished building in a Uighur neighborhood. The Chinese government says it is taking down buildings to build earthquake-resistant structures, but Mr. Sakamaki insists the government is posturing.Mr. Sakamaki works as an outsider, and his photos offer glimpses of indecision and unease.

而同样是在新疆,一个维吾尔族男孩站在一个被拆毁的维吾尔族社区中,看着地上的碎石瓦砾。中国政府称拆毁这些建筑是为了修建抗震房屋,但Sakamaki认为政府只是在做样子。作为一个局外人,Sakamaki的照片展现了迟疑与忧虑。

Mongolian men riding a motorbike fleck an immense field. The face of a polar bear pelt looms before the uniforms of China’s last emperor, Puyi. An unemployed man, close and out of focus, partly obscures high-rise buildings being erected around a memorial square, dedicated to the region’s iron industry.

蒙古人骑着摩托车驶过巨大的田野。北极熊熊皮的背后隐约可见中国末代皇帝溥仪的皇服。一个近景而虚焦的工人肖像,部分遮挡了在纪念广场附近林立的高楼。他曾为这个地区的钢铁行业做出贡献,现在已经下岗。

This work is Japanese in style, Mr. Sakamaki says, and much more personal than traditional photojournalism. He sees China’s struggle for identity within himself and says that while the project takes place in China, the same ideas of independence and conformity are universal.“Japanese culture is very personal,” he said. “So I felt maybe I put my personality, my identity, my own Japanese history, and also my own identity as a human being, combined.”

Sakamaki说,这组照片很日式,与传统摄影报道相比,带有强烈的个人风格。他在自己身上看到中国对于身份认同的努力与挣扎。他说,虽然这组照片在中国拍摄,但对于自主与遵从的想法是全球性的。”日本文化是非常个人化的,所以我认为也许我应该在作品中融入更多我的个性,我的身份,我自己的日本历史,我自己作为人类的身份认同。”