Ambitious, obsessive and empirical, Wedgwood raged at his “dilatory, drunken, Idle, worthless workmen”, then set about reforming them.

韦奇伍德是有野心的、痴迷的,且信奉经验主义,对他“拖拉、酗酒、懒惰、毫无价值的工人”感到愤怒,于是着手改造他们。

Before the Industrial Revolution came the “industrious revolution” in household productivity.

工业革命之前,家庭生产力发生了“勤劳革命”。

Wedgwood wrote that he wanted “to make such Machines of the Men as cannot Err”.

韦奇伍德写道,他希望“人类制造出不会犯错的机器”。

He trained and chivvied, tweaked and experimented, building new factories for his pots and a model village for his workers.

他训练、督促、调整和试验,为他的陶罐建造新工厂,为他的工人创造了一个模范村庄。

Vases in their thousands, then in their tens of thousands, began to emerge from the Wedgwood production line.

数千的花瓶,接着,数万的花瓶,开始从韦奇伍德的生产线上涌出。

The history of pots matters because they do.

陶罐的历史之所以重要,是因为它们确实如此。

Pick one up and in its lines you can trace trade routes and chronicle empires.

拿起一个陶罐,在它的线条中,你可以寻迹追溯贸易路线和帝国的历史。

The rise and fall of Rome can be charted in the words of its historians, but it is observed more accurately in the rise and fall of the Roman pot trade.

罗马的兴衰可以用历史学家的文字描绘出来,但从罗马陶罐的兴衰中来观察它更为准确。

At its imperial peak Roman ceramics — cheap, trademarked, perfect — were shipped everywhere from Africa to Iona; after Rome fell it would take centuries for European pottery to recover such excellence.

在罗马帝国的鼎盛时期,罗马陶瓷——廉价的、有商标的、完美的——被运往从非洲到爱奥纳岛之间的各个地方;罗马帝国陷落后,欧洲陶器花了几个世纪的时间才恢复到如此卓越的水平。

Examine a cup made under China’s Han dynasty, meanwhile, and you will see not just fine design but an advanced bureaucracy.

与此同时,仔细观察中国汉朝时期制造的杯盏,你会发现它不仅设计精美,而且极具官僚气息。

A single piece can be inscribed not just by the six craftsmen who made it, but by the seven officials who inspected it.

一件作品不仅可以由制作它的六名工匠题字,而且可以由七名检查它的官员题字。

Pots contain worlds.

陶罐中蕴含世界。

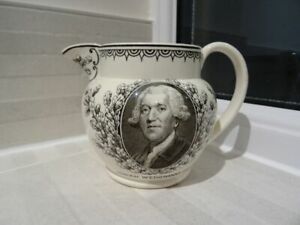

In his lifetime some of Wedgwood’s most popular products were his medallions: little ceramic circles embossed with profiles of famous figures, such as Aristotle, John Locke and Voltaire.

韦奇伍德一生中最受欢迎的一些产品是他的圆形浮雕:圆形陶片上雕刻有著名人物的肖像侧影,如亚里士多德、约翰·洛克和伏尔泰。

Peer at a piece of Wedgwood, and you can still be astonished by the brilliance of the individual engravings — by the curl lying on this king’s neck, or the realistic line of that philosopher’s nose.

仔细看一看韦奇伍德的作品,你仍然会为其精美绝伦的雕刻而惊叹——国王脖子的弧度,或者哲学家鼻子那里逼真的线条。

Yet as Mr Hunt’s elegant biography shows, to focus on these exquisite details is slightly to miss the point.

然而,正如亨特这本精妙的传记所展示的那样,专注于这些精美的细节有些搞错了重点。

Wedgwood’s genius lay not in the creation of individuality, but in the erasing of it.

韦奇伍德的天才不在于创造个性,而在于消除个性。

He wanted to make machines of men, and he did.

他想把人变成机器,他做到了。

And then his machine-men churned out umpteen more manufactured men in their turn, Voltaires and Aristotles rolling off the production line in their hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands, until the world was astonished no more.

接着,他的机器工人又生产出无数的人造人,伏尔泰和亚里士多德从生产线上滚落下来,成百上千,成千上万,直到世界不再感到惊讶。

译文由可可原创,仅供学习交流使用,未经许可请勿转载。