Finance and Economics;German macroprudential reforms;Beware Teutonic caution;

The Bundesbank should not exert its new clout too zealously;

The European Central Bank (ECB) decided a year ago to hold this week’s monetary-policy meeting in Barcelona, but the timing turned out to be perfect. Spain is in the crosshairs of the markets, not least because of budgetary overruns by regional governments such as Catalonia’s. And the contrasting economic fortunes of beaten-up Spain, where the jobless rate has reached 24%, and resilient Germany, where it is below 6%, exemplify the difficulty of finding the right monetary policy in a currency union of 17 members.

The ECB’s meeting on May 3rd (after The Economist went to press) was not expected to change its monetary stance. Behind the scenes, however, there are acute tensions within its 23-strong governing council, made up of six board members and the heads of the 17 national central banks. In particular Jens Weidmann, the president of the powerful German Bundesbank, opposed the decision to cut interest rates to 1% in December, and frets about the adequacy of the collateral against which the ECB has lent so much money to banks in recent months.

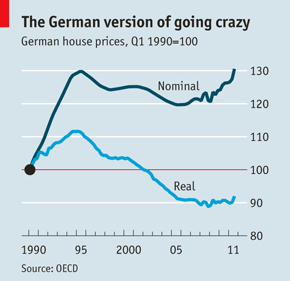

Among other things Germany’s top central banker wants to avoid a home replay of the credit and property boom whose excesses have been so harmful in Spain. Loose monetary policy makes him nervous about the possibility of a property bubble in Germany. After a long period when house prices fell and then stagnated, they have picked up in the past couple of years (see chart). Homebuilding orders are up by a fifth on a year ago.

Such anxiety looks premature: house-price rises represent a thawing in the property permafrost rather than a market on fire. But if Mr Weidmann is minded to take pre-emptive action, he will soon have the means to do so. At present the Bundesbank can preach about risks to financial stability but it cannot impose counter-measures such as setting higher capital requirements for banks or putting constraints on specific types of lending such as mortgages. The authority for implementing these steps lies with BaFin, Germany’s bank supervisor (which is assisted on the ground by Bundesbank staff).

This will change under new proposals to set up a joint committee, which will have representatives from the finance ministry and BaFin, but which will give the Bundesbank the leading role and enable it to push through binding directives. The legislation won’t come into force until next year, but since it is designed to strengthen his hand, Mr Weidmann would probably be able to get his own way before then.

The reform is part of a general move to add “macroprudential” instruments to the toolkit of central banks, allowing them to choke off credit excesses while monetary policy is set for the economy as a whole. If anything, Germany is treading less far down this path than some other countries—in Britain, for example, the Bank of England will call the shots through a powerful new Financial Policy Committee, which has already started work. Such powers should be particularly useful in the euro area, providing countries with a national lever to pull if their banks are getting too festive (though Spain’s pre-crisis policy of “dynamic provisioning”, designed to get local banks to set aside more provisions in the good times, cautions against investing too much hope in macroprudential tools).

But in the current climate there is also the danger that such regulations may be used in bigger economies to grab back power from the ECB. By reducing credit availability national central banks can contravene the euro zone’s wider monetary stance. Speaking in New York in late April Mr Weidmann said that if monetary policy becomes too expansionary for his home country, “Germany has to deal with this using other, national instruments.” If Mr Weidmann does use his new powers overzealously that could dash one of the few remaining hopes for the hard-hit peripheral economies: a strong recovery in the euro area, led by Germany.