Books and Arts; Book Review;Nuclear warfare;Conscientious objector;

文艺;书评;核战争;良心反对者;

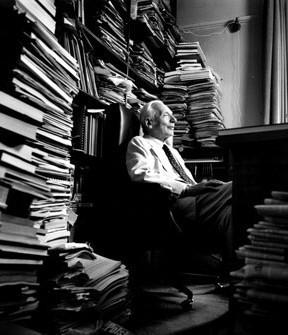

Keeper of the Nuclear Conscience: The Life and Work of Joseph Rotblat.

持有核良知的人:约瑟夫·罗特布拉特的工作与生活;

Many of the scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project, America's programme to build an atom bomb during the second world war, had misgivings about their work. After the detonation of the first test bomb in 1945, Robert Oppenheimer, the programme's director, later claimed to have recalled a line from Hindu scripture: “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” His colleague Kenneth Bainbridge was pithier: “now we're all sons of bitches,” he muttered.

在二战期间从事原子弹制造的曼哈顿计划中,有很多科学家对自己所做的事情满怀忧虑。1945年第一课原子弹试爆之后,该计划的执行官罗伯特奥本海默引用了印度经文的一句话:“我将成为死神,万物的毁灭者。” 而他的同僚肯尼斯 班布里奇更为直截了当:“如今我们都是狗杂种了。”

Joseph Rotblat, a Polish-born physicist, had stronger reservations than most. He had been disturbed to overhear the American general in charge of the project admit that the real point was not to pre-empt the Nazis—whose own atomic-bomb project had got nowhere—but to intimidate the Soviets, the Americans' wartime allies. In 1944 Rotblat left the programme to return to Britain, where he had taken refuge from occupied Poland, and resolved to put his expertise to more humane use. He swapped theoretical physics for the medical kind and began a life of vigorous opposition to nuclear weapons. A friendship with Bertrand Russell, a British philosopher, led to the founding of the Pugwash conferences on nuclear disarmament.

物理学家约瑟夫罗特布拉特出生于波兰,比其他多数人都有更多的保留意见。在无意得知曼哈顿计划将军承认这项计划的真实目的不是对纳粹先发制人,而是恐吓美国战时的盟友苏联时,他心感不安。当然,纳粹的原子弹计划也不了了之。1994年罗特布拉特退出曼哈顿计划回到了英国,在那得到了已被占领的波兰的庇护,便从此致力于人道主义的事业。罗特布拉特从理论物理转向了医用类,开启了自己极力反对核武器的人生。他与好友伯兰特 罗素(英国哲学家)一道开辟了帕格沃什会议核裁军的道路。

Andrew Brown's biography traces the history of both Rotblat as a man and Pugwash as a group. That dual focus is occasionally jarring—at one stage he moves from a discussion about test animals in Rotblat's London hospital to a sweeping history of attempts to ban nuclear testing. Acronyms, committees and minor players come thick and fast. Readers can expect to make frequent trips to Wikipedia.

安德鲁布朗写的传记就追溯到了洛特布兰特和帕格沃什会议的源头,但是这两者结合起来有时显得不和谐:在一个阶段,作者从讨论罗特布拉特在自己伦敦的医院里进行动物实验,又跳到了他反对核试验的风光历史中。另一层面,作品中频繁穿插出现了大量的缩略词,委员会和不重要的人物的名字。要读下来还要指望维基百科。

But the story itself is good enough to shine through. The idea behind Pugwash (named for the remote hamlet in Nova Scotia where the early meetings were held) was that scientists—particularly nuclear scientists—were uniquely suited to grapple with the problems of the nuclear-armed world which they had helped bring into being. They understood the details and were prone to thinking bold thoughts. As an international scientific group, Pugwash was a useful counterpart to the fearful nationalism shaping politics. Delegates debated the theory of nuclear deterrence, pondered the potential damage of a nuclear war, and agitated for disarmament and the abolition of nuclear weapons.

但是故事本身就有很多亮点贯穿始终。帕格沃什(早期会议在新斯科舍省召开时,以一偏远小村庄的名字命名)会议的主旨是让科学家们与他们亲手建起的核武器世界斗争,尤其是这些核专家再适合不过了,因为这些专家对核制造了如指掌,而且他们想法奇特大胆。参会代表们一起讨论核威慑的理论,思考核战争的潜在危险,并倡导核裁军和销毁核武器。作为一个国际科学小组,帕格沃什会议成为恐怖的民族主义塑造政治的有用对口。

Many of the attendees had the ear of their national governments. Over the years the Pugwash conferences evolved into a crucial source of backdoor communications between the superpowers, penetrating the fog of mistrust that characterised the cold war. The foundation of the Partial Test Ban Treaty (which banned aboveground nuclear explosions) and various other nuclear disarmament treaties was laid largely at Pugwash.

许多出席者都是国家政府的亲信,会议也多年来演变成超级大国私下互访的重要来源,冲破了由冷战披上的国家之间互不信任的迷雾。“部分核禁试条约”(禁止地面核爆炸)和许多其它核裁军条约主要是在帕格沃什会议上签订的。

For Rotblat, though, these were only partial victories. Throughout his life, his goal remained a world free of nuclear weapons. His experience of the second world war had a lasting impact (his wife may have been murdered at Belzec, an early Nazi death camp). He was not convinced by the argument that the threat of nuclear weapons would ultimately prevent war. The logic of deterrence, and later of mutually assured destruction—which presumes that war between nuclear-armed nations is impossible, because the mutual annihilation ensures that neither side could win—applies only to rational actors. Had Hitler had the bomb, Rotblat argued, “his last order from the bunker in April 1945 would have been to use it on London even if it meant terrible retribution to Germany. This would have been part of his philosophy of Gotterdammerung.”

对于罗特布拉特而言,这些仅是他人生长河中的小小胜利,他的目标是在世界范围内消除核武器。二战经历对他的影响让他久久不能释怀,战时自己的妻子在贝尔塞克一个纳粹死亡集中营被杀害。他从不相信有了核武器的威胁就能最终抑制战争。核威慑逻辑以及同生共亡的理论(该理论持有者认为核武器国家间是不会有战争的,因为相互之间的灭亡会使任何一方都无法赢得战争)只适用于理性行为者。如果希特勒有了核弹,“即使核弹是德国的报应,也许1945年4月希特勒在自己的堡垒发出的最后命令就是用核弹炸掉伦敦。这或许也会成为他‘诸神的黄昏'哲学的一部分。”罗特布拉特争论道。

Readers may now find Rotblat's idealism naive. Talk of total nuclear disarmament seems idle in a world with nine nuclear powers and a simmering crisis over a possible tenth. Yet the pessimism of the 1950s has proved overblown as well: nuclear weapons have proliferated much more slowly than many feared at the dawn of the atomic age, and stockpiles have dwindled since the height of the cold war. For Rotblat, to be accused of idealism was no bad thing. He liked to quote his friend Russell: “do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.”

读后如今可能觉得罗特布拉特的理想简单幼稚,对于一个有九个核电站,还有一个蠢蠢欲动,马上要建的世界,聊聊完全的核裁军简直是一场空谈。然而,20世纪50年代也对核武器的悲观情绪进行了过度渲染,事实证明:核武器扩散速度比在人们担心的原子能初期放慢了许多,核物质储备也自冷战高潮以来减少。对罗特布拉特而言,背上理想主义的罪名也不是个坏事。他喜欢引用好友罗素的话说:“不要为自己持独特看法而感到害怕,因为我们现在所接受的常识都曾是独特看法。”