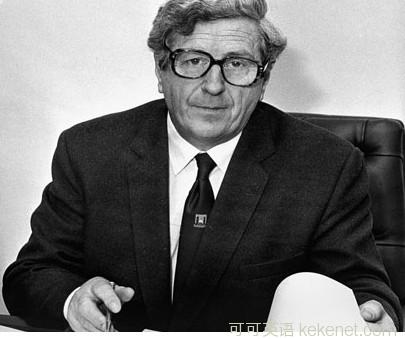

Obituary;Garret FitzGerald;

Garret FitzGerald, statesman, philosopher, journalist and lover of numbers, died on May 19th, aged 85;

If you had the good fortune to sit next to Garret FitzGerald at dinner—wrapped round by his natural warmth and curiosity, as well as numbed by the sheer volume of Dublin-tinctured words that tumbled out of him—you might learn many dozens of mind-bogglingly arcane facts. The quickest way to fly from Reykjavik to Vilnius in 1960, a skill he had honed in his first proper job as an analyst for Aer Lingus; the route of the now-defunct railway from Farranfore to Reenard via Cahersiveen, the fruit of his love of all train timetables; the relative popularity over time of his own Fine Gael party and the rival Fianna Fail in county councils the length and breadth of Ireland, derived from an obsession with opinion polls so immense that journalists were cautioned not to mention them; and the precise geographical pattern of the decline in the use of Irish between 1770 and 1870, compiled from old census volumes which he would prop on the car dashboard when being driven, on constituency visits, from place to place.

What modesty would restrain him from telling you—even in the 674 small-print pages of his autobiography—was the precise route by which Ireland, while he was cheerfully inhabiting the corridors of the Seanad and the Dail, moved away from sterile, irredentist sectarianism to become a more open and tolerant place; how the sombre dominance of the Catholic church began to recede from the country's moral life; how Ireland opened itself alike to Europe and to foreign investment, eventually finding it could leap off like a tiger; and, most wonderful and difficult of all, how North and South began to accommodate and make peace with each other, to such a degree that as he lay dying Queen Elizabeth was in Dublin Castle, trying out a line of Gaelic.

His own contribution, because it was the start of these processes, often looked like failure. His referendum to amend slightly the law on abortion was shot down, his referendum to bring in divorce resoundingly defeated; but he had succeeded in broaching the subjects in a civil way. On Northern Ireland, the 1973 Sunningdale power-sharing agreement swiftly collapsed, and his New Ireland Forum, in which constitutional parties from both sides were to meet and talk together of the pluralist, inclusive Ireland he longed for, was ruthlessly scorned by Margaret Thatcher. (“Out, out, out,” she cried, demolishing all its proposals one by one; it wasn't what she said, he reflected later, but the tone in which she said it, so sharp and condescending.) Even the Anglo-Irish agreement of 1985, in which Britain acknowledged for the first time the Republic's interest in the North, was pictured by unionists as betrayal and by terrorists as encouragement. In fact it was a small, determined step towards the Good Friday agreement 13 years later.

A mislaid overcoat

He had the ideal background for conciliation, with a Catholic father from the South and a Protestant mother from the North (though it was she who taught him his catechism, forbearing only to instruct him how to sign himself at the gospel). Sectarianism was so foreign to him that when he met rank prejudice, he often burst out laughing. Politics was in his blood, his father having been in independent Ireland's first government in 1922; though he himself wandered into it from academia, reluctant to give partisan speeches in the open air or at dance halls, and quite inept at the plotting and manipulation so dazzlingly displayed by his Fianna Fail nemesis, Charles Haughey. Though he was foreign minister from 1973-77 and taoiseach twice, in 1981-82 and 1982-87, he remained somehow an innocent, mislaying as he travelled overcoat, pyjamas, watch; and not realising, so carried away was he with his theories for redistributing wealth in Ireland, that to put value-added tax on children's shoes might spell suicide at the polls.

Economics was a relatively late interest. He said he learned it at the Irish Times, where he wrote to the end of his life a Saturday column full of figures under the pen-name “Analyst”. Over 50 years, he reckoned, he produced 2,250,000 words for the Times (besides providing copy, briefly, for The Economist). History and French were his degree subjects, and his verbosity in French a source of pride. He embraced the European Economic Community not just because it let Ireland reach over Britain to the world, but also because it gave him the excuse, before meetings in Brussels, to discuss with Fran?ois Mitterrand some puzzling lacunae in the Catholic intellectual tradition of 19th-century France.

He was tender and naive, losing his life-savings on an unwise investment in 1992; yet he was also tough. Meeting the families of IRA hunger-strikers in the 1980s, he would be sympathetic as ever, but would never let himself be swayed by terrorists or “crawthumpers”. Though mocked as otherworldly, he stuck to his crusade for a “new Ireland”—reunified or not, as the majority in the North wanted it—in which Catholic and Protestant identities would be equally celebrated. For, when all was said and done, he was a statistician first; and when shown any air-traffic controller's chart he could tell, to a high degree of accuracy, that at such-and-such a time and place the different flightpaths, no matter how divergent, were bound to cross.