This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Susanne Bard.

In 2006 a 26-year-old California man named Uriah Courtney was sentenced to life in prison for kidnapping and rape, despite having an alibi for the time the crimes were committed.

"And there were two witnesses. They saw a lineup in the police station, and they both identified the same person. And he was convicted, entirely based on those two eyewitness accounts."

Salk Institute for Biological Studies neuroscientist Tom Albright. He says years later, the California Innocence Project looked into the case.

"And it turns out that the DNA that was found at the crime scene was not the DNA of Uriah Courtney."

After eight years behind bars, Courtney was set free. But his case is not unique.

"There are now hundreds of cases in which individuals have been exonerated based on this post-conviction DNA analysis."

Most of these innocent people were sent to prison because witnesses misidentified them.

"Somebody picked them out of a lineup, and that information was taken seriously by the police. And the jury believed it."

Why do witnesses sometimes get it so wrong? Albright explains that our memory for visual events is notoriously flawed.

"If somebody tells us that they saw something, we figure, well, it must be true. They saw it with their own eyes."

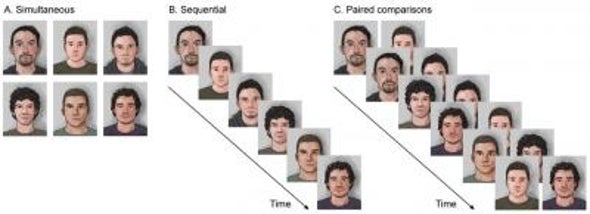

Lineups typically show witnesses photos of six faces—five of innocent people and one of the suspect.

"The eyewitness is simply asked to identify any person that they remember from the crime scene."

But only having them pick their top choice doesn't account for how well the witness remembers that face. This issue can result in errors.

Albright's team thinks there's a better way—by tapping into the strength of the witness's memory. In an experiment, they had volunteers watch a clip of a grisly crime scene from an obscure Hollywood movie.

The next day, these study subject "witnesses" viewed a six-person lineup that showed just two faces at a time. Think of an eye test: Better now—or now?

"So on each pair, the witness will vote for one or the other of the faces: Which one looks more similar to the person you remember from the crime scene? We then tabulate that vote. And the face that has the largest number of votes is the winner."

Compared to traditional lineup techniques, the two-faces-at-a-time method led to a less biased and more accurate identification of the fictional perpetrator.

"People are far better at making relative judgments than they are at making absolute judgements."

The study is in the journal Nature Communications.

The researchers think their approach to lineups has the potential to reduce wrongful convictions, resulting in more justice for all.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American's 60-second Science. I'm Susanne Bard.