Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION -- American history in VOA Special English. The battle between the North and the South spread in the summer of eighteen sixty-one. Union soldiers fought pro-southern rioters in the streets of Baltimore and Saint Louis. A Confederate supporter shot and killed a young officer from the North. Untrained soldiers from both sides fought in the mountains of western Virginia. So far, though, the fighting had not claimed many lives. But very soon, the battle would become fierce. This week in our series, Frank Oliver and Jack Weitzel continue the story of the American Civil War. The old general who commanded the Union forces, Winfield Scott, did not want to rush his men into battle. Scott believed it would be a long war. He planned to spend the first year of it getting ready to fight. He had an army of thousands of men, and it would get much larger in coming months. But this army was not trained. His soldiers were civilians who knew nothing about fighting a war. General Scott needed time to make soldiers of these men.

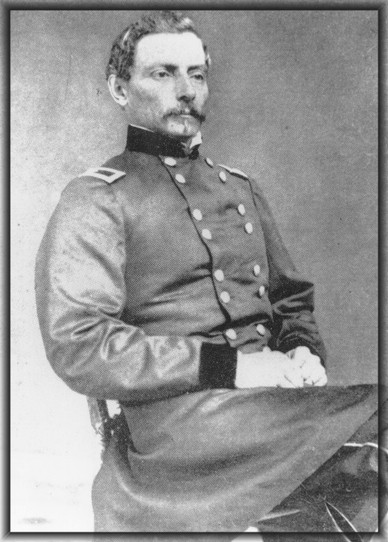

He also needed time to organize a supply system to get to his forces the guns, bullets, food, and clothing they would need. Without supplies, his army could not fight very long. There were many in the North, however, who thought Scott was too careful. It was true, they said, that Union forces were untrained. But so were those of the South. And the Confederacy's supply problems were even greater than those of the Union. The South had much less industry and fewer railroads. It could not produce as much military equipment, and it could not transport supplies as easily as the North could. In the early months of the war, Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president, did not even have guns enough for the men in his army. Those who demanded immediate action expected a short war. They said Scott should take the army and march to Richmond. They were sure that if Union forces seized the Confederate capital, the southern rebellion would end. Northern newspapers took up the cry, "On to Richmond!" Political leaders began pressing for a quick northern victory. Public pressure forced the army to act. For more than a month, General Irvin McDowell had been building a Union army in northern Virginia, just across the Potomac River from Washington. He had more than thirty thousand men at bases in Arlington and Alexandria. Late in June, McDowell received orders: "March against the Confederate Army of General Pierre Beauregard."

Beauregard had twenty thousand soldiers at Manassas Junction, a railroad village in Virginia less than fifty kilometers from Washington. McDowell planned to move on Manassas Junction July ninth, but was delayed for more than a week. He planned the attack carefully. McDowell was worried that another large Confederate force west of Manassas Junction might join Beauregard's army. This force, led by General Joe Johnston, was in the Shenandoah Valley near Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Across from Harpers Ferry, in Maryland, was a Union army almost twice the size of Johnston's. It was ordered to put pressure on Johnston's force to prevent it from helping Beauregard. General Beauregard received early warning from Confederate spies that McDowell would attack. Much of his information came from a woman, Missus Rose O'Neal Greenhow. Missus Greenhow, a widow, was an important woman in Washington. She knew almost all the top government officials. And she had friends in almost every department of the government.

The beautiful Missus Greenhow also had some very special friends. One was Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts. He was chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. Another special friend was Thomas Jordan, a Confederate colonel in Beauregard's army. Jordan asked Missus Greenhow, soon after the war started, to be a spy for the South. She agreed and sent much valuable information about Union military plans. Early in July, she sent word to Beauregard that he would be attacked soon. She also sent a map used by the Senate Military Affairs Committee showing how the Union army would reach Manassas Junction. Then, on the morning of July sixteenth, Missus Greenhow wrote a nine-word message. She gave it to a man to carry to Beauregard. The Confederate general received it that evening. It said: "Order given for McDowell to march upon Manassas tonight." Beauregard sent a telegram to Richmond. He told the Confederate government that McDowell was on the way. He asked that Johnston's ten thousand-man force in the Shenandoah Valley join him for battle. He was told to expect Johnston's help.

But Johnston's army was threatened by a large Union force that entered Virginia from Maryland. Led by General Robert Patterson, the Union troops moved toward the smaller Confederate force. They were not really interested in fighting Johnston. But they did want to prevent him from reaching Beauregard. Johnston knew he could not defeat Patterson. So he decided to trick him. While most of his army withdrew and prepared to join Beauregard, Johnston sent a small force to attack Patterson's army. Patterson believed Johnston was attacking with all his troops. He stopped moving forward and prepared to defend against what seemed to be a strong Confederate attack. By the time the trick was discovered, Johnston and most of his troops were at Manassas. General McDowell's huge Union army left Arlington on the afternoon of July sixteenth. It was a hot day, and the road was dusty. The march was not well organized, and the men traveled slowly. They stopped at every stream to drink and wash the dust from their faces. Some of the soldiers left the road to pick fruits and berries from bushes along the way. To some of those who watched this army pass, the lines of soldiers in bright clothes looked like a long circus parade.

Most of these men had not been soldiers long. Their bodies were soft, and they tired quickly. It took them four days to travel the forty-five kilometers to Centreville, the final town before Bull Run. The battle would start the next morning -- Sunday, July twenty-first. The road from Washington was crowded early Sunday morning with horses and wagons bringing people to watch the great battle. Hundreds of men and women watched the fight from a hill near Centreville. Below them was Bull Run. But the battleground was covered so thickly with trees that the crowds saw little of the fighting. They could, however, see the smoke of battle. And they could hear the sounds of shots and exploding shells. From time to time, Union officers would ride up the hill to report what a great victory their troops were winning. In the first few hours of the battle, Union forces were winning. McDowell had moved most of his men to the left side of Beauregard's army. They attacked with artillery and pushed the Confederate forces back. It seemed that the Confederate defense would break. Some of the southern soldiers began to run. But others stood and fought.

One Confederate officer, trying to prevent his troops from moving back, pointed to a group led by General T. J. Jackson of Virginia. "Look!" He shouted. "There is Jackson, standing like a stone wall! Fight like the Virginians!" The Confederate troops refused to break. The fighting was fierce. The air was full of flying bullets. A newsman wrote that the whole valley was boiling with dust and smoke. A Confederate soldier told his friend, "Them Yankees are just marching up and being shot to hell." Neither side would give up. Then, a large group of Johnston's troops arrived by train and joined in the fight. Suddenly, Union soldiers stopped fighting and began pulling back. General McDowell and his officers tried to stop the retreat, but failed. Their men wanted no more fighting. The fleeing Union soldiers threw down their guns and equipment, thinking only of escape. Many did not stop until they reached Washington. It was a bitter defeat. But it made the North recognize the need for a real army -- one trained and equipped for war. President Abraham Lincoln gave the job of building such an army to General George McClellan.