This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

If you've ever used a digital assistant like Siri or Alexa, you know the back and forth doesn't quite have the same rhythm as real human-to-human conversation. The pauses are just a little too long.

"We feel this sort of awkward silence building up." Sebastian Loth, a research psychologist at the University of Bielefeld in Germany. "If I ask you something and you just don't respond, it feels like, oh my god this silence is almost killing the room and you can feel it literally building up. So we try to avoid that. And that's the kind of effect that you're seeing with Siri taking a second to respond, you're kind of feeling odd about it."

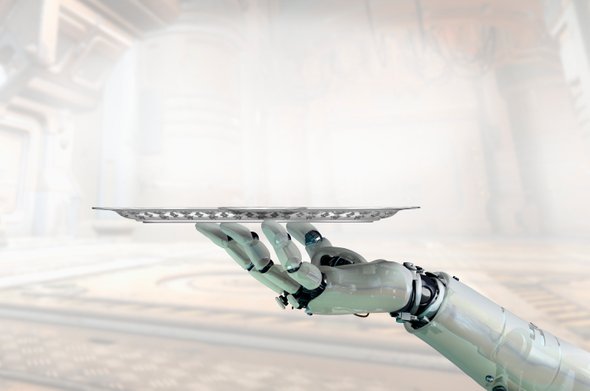

To study how humans are able to have such fluent, sometimes even overlapping, conversations, Loth and his team set up what's called a "Ghost in the Machine" experiment, in a barroom situation. Real human customers bellied up to a bar, where a robot bartender was waiting. The robot was actually controlled by human operators behind the scenes, who could see and hear the customers through the robot's eyes and ears.

Then Loth and his team observed how the human operators behaved during a couple hundred orders. They found that when the customers started a phrase with "What," the human operators quickly triggered the robot to repeat the offerings of the bar, like "We have coke, orange juice and water," rather than waiting for customers to complete the sentence. But if the customers began a sentence with "I'd like" or "I want," the human operators tended to hesitate, to listen for what came next, rather than acting quickly—and perhaps incorrectly.

"What we found was that they distinguish between the type of request. And more specifically by the error or cost of that. If I misunderstand you and give you the wrong drink that is actually quite an awkward situation. Because I kind of have to apologize, take the drink away from you, and replace it with the appropriate one. So it's a lot of action and maneuvering involved and it's quite embarrassing if the bartender gets it wrong." The details are in the journal PLOS ONE.

Loth says cataloguing interactions like these might help future robots better navigate the continuum between certainty and time: to be able to act quickly on limited evidence, to provide speedy service, but without getting things wrong so often that it annoys the user.

And no, he doesn't really envision replacing human bartenders with robots. "What you'll probably see is that stuff like that will be incorporated in ticket machines, or in booking systems, or in request systems like Siri where you're asking for a route to be displayed on the phone."

After all, he says, a real human bartender does a lot more than serve drinks.

"Hey, buddy, why the long face?"

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.