This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

Thirty-nine years ago, Voyager 1 swung by Jupiter on its journey to interstellar space. As it did, it picked up spooky low-frequency radio signals like this. (CLIP: Voyager 1 whistlers)

The whistlers, as they're known, were radio broadcasts from unusual, natural antennas: lightning bolts, which act like radio transmitters, with current moving through a channel.

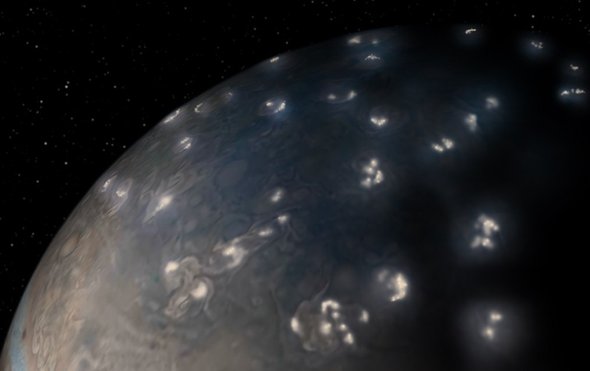

Along with photos of the dark side of the planet, the whistlers confirmed the existence of lightning on Jupiter. But the limited observations made it hard to pin down where electrical storms gathered... and the bolts were thought to be rare, compared to Earth.

Now the Juno spacecraft has detected the first high-frequency radio signals, and 1,600 new whistlers (CLIP: Juno whistlers)..., which together suggest lightning on Jupiter is much more common than scientists thought. And a lot more similar to Earth lightning, too. The discharges also appear to be between clouds containing liquid water and others containing water ice..., the same kind of conditions for cloud-to-cloud lightning here on Earth.

The findings appear in the journals Nature and Nature Astronomy.

There is one twist to this Jovian weather story: Jupiter's lightning storms congregate near the planet's poles, not its equator—the opposite of Earth. And a detail that makes this familiar phenomenon still seem a bit otherworldly.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.