Hari Sreenivasan: We turn now to an art exhibit here in New York city that examines the relationship between the rise of nationalism and censorship of the arts. NewsHour weekend's Ivette Feliciano reports.

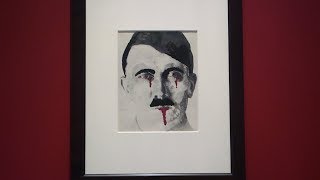

Ivette Feliciano: Countries from Poland to Hungary to Turkey are experiencing a rise in nationalism and the effects it can have on free speech. While this turmoil goes on, a new exhibit at New York's Neue Galerie, "Before the Fall," examines art produced in Germany and Austria under the Third Reich and what can happen to a culture when free speech is curtailed in the extreme.

Dr. Olaf Peters, Art historian, Germany's Martin Luther University: The idea behind the exhibition is to think about how artists reacted to political, historical circumstances and how they work, evolve during the 1930s. So, it was really like thinking about, is there potential in art to reflect on historical circumstances?

Ivette Feliciano: Dr. Olaf Peters is an art historian at Germany's Martin Luther University and the exhibit's curator. The show is a continuation of two previous Neue shows. "Degenerate Art" examined works that the Nazi party publicly denigrated while "Berlin Metropolis" looked at the rich artistic culture of Germany's capital in the 1920s.

Adolf Hitler's Third Reich purged the modern art world after coming to power in 1933. It raided the influential Bauhaus art school and shut it down. It did the same to the modern art wing of the German National Gallery. Hitler banned many artists from creating art altogether.

Dr. Olaf Peters: You had an extremely strong and rich art scene during the 1920s in Germany. For me, the question was always, what happened to this art scene?

Ivette Feliciano: Peters says that many artists camouflaged their beliefs using conventional art forms. Still lifes and portraits became heavy with symbolism. Landscapes, like the 1936 painting "Expectation" by German artist Richard Oelze, depicted dark and foreboding scenes.

Dr. Olaf Peters: It's a little bit apocalyptic landscape on the one side if you have, on the other side, a group of people standing there and looking maybe into a dark or unknown future.

Ivette Feliciano: Those artists who did not conform could not find a safe venue for their work. How was their work received at the time by the public?

Dr. Olaf Peters: Some are so overt when it comes to critique of those circumstances, the living conditions of the Third Reich, that it's impossible to show them.

Ivette Feliciano: One artist who chose self-exile was the German painter Max Beckmann, who left Germany for the Netherlands in 1937. There he painted a work called "Birds' Hell," which contains political references to the Nazi party.

Dr. Olaf Peters: It was painted one year after Max Beckmann had left Germany. And in Amsterdam, he made the decision to create this allegory of his country where you can see the birds torturing, for example, saluting.

Ivette Feliciano: Some artists paid the ultimate price for their work. One was a Jewish-Austrian artist named Friedl Dicker-Brandeis.

Dr. Olaf Peters: She was highly political. She studied at the Bauhaus in Weimar in Germany, went back to Austria and developed some, say, political montages or collages in the early 1930s. But she was captured. She depicted some interrogations which are really touching because you can see what torture meant. And she was finally brought into an extermination camp and was killed.

Ivette Feliciano: Dr. Peters says that visitors to the exhibit may view these older works in a new light, following a recent nationalist surge in europe.

Dr. Olaf Peters: The situations are different, and history is not repeating itself. But, of course, you have to learn from history, maybe think about how to avoid developments which are not a little bit similar, not identical, and, yeah, and be aware of your responsibility.