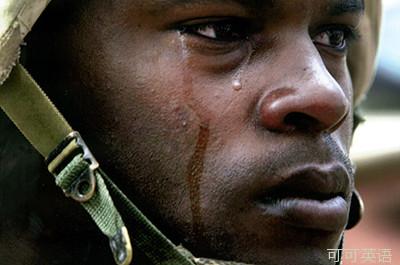

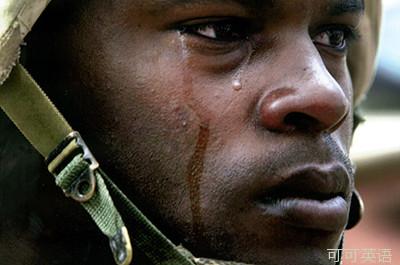

War is hell. And for many soldiers, the experience leaves lasting scars. And not just physical ones. A subset of veterans develop post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. But it might not be only the horrors of battle that make them susceptible. According to a study in the journal Psychological Science echoes of childhood abuse may contribute.

战争就是地狱。对于许多军人来说,战争的经历给他们留下了永远的创伤,并不仅仅是指身体上的创伤。根据一项发表在《心理科学杂志》上的题为“虐待儿童可能造成的影响”的研究,一小部分退伍军人患上了创伤后应激障碍,略作 PTSD,然而对战争的恐惧并不足以使他们患上这种心理疾病。

Psychologists assessed the mental health of hundreds of Danish soldiers before, during and eight months after they were shipped to Afghanistan. Turns out the vast majority, some 84 percent, were resilient, showing no undue signs of stress at any time. A small number, about 4 percent, developed PTSD, with symptoms that showed up when the troops returned home.

心理学家们评估了上百名丹麦士兵被派往阿富汗战场之前,期间以及八个月之后的心理健康水平。结果证明,大多数(大约84%)士兵的精神适应力强,在任何时候都没有迹象显示他们承受着过度的压力。在部队撤回后,一小部分士兵(大约4%)出现了创伤后应激障碍的症状。

When the researchers compared those two groups, they discovered that the cohort with PTSD had not been exposed to more battlefield trauma—but they were more likely to have experienced violence or abuse in civilian life, particularly as a child.

当研究人员比较这两组士兵时,发现患上创伤后应激障碍的战士并没有更多地接触到战地创伤,但是他们在平常生活中经历过暴力或者虐待的可能性更大,尤其是在儿童时期。

For the remaining soldiers, being deployed actually helped: something about being part of the team quelled the anxiety they started out with. That finding suggests that PTSD is not uniform, even for those in uniform. And that one man's poison may be another man's cure.

对于从战场上幸存的战士来说,听从指挥实际上有所帮助:这种成为团队一员的归属感平息了一开始就有的焦虑心态。这个发现证明:即使对那些身穿制服的士兵,创伤后应激障碍也并不完全一样。这就所谓的我之毒药,彼之良药。