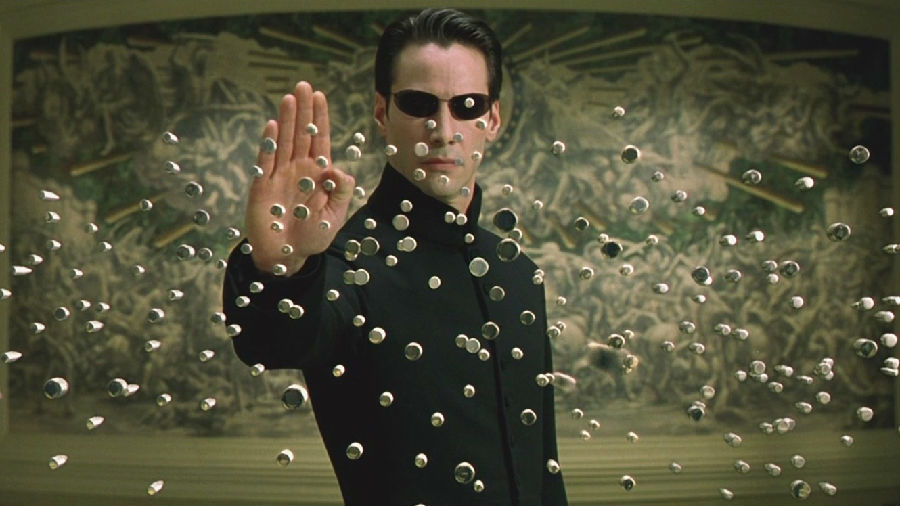

If you Google “best slo-mo scene ever,” you'll find the Matrix “lobby scene” over and over again.

如果你上谷歌搜“史上最赞的慢镜头”,《黑客帝国》“大堂枪战镜头”会反复出现在搜索结果里。

It is actually a 3 minute 13 second tapestry of 74 apparently normal clips and just 35 slow motion ones.

那个片段其实是一个3分13秒的混剪,其中有74个明显的正常速度镜头,慢镜头其实只有35个。

Yet this is what we remember.

然而,它还是给我们留下了这样的印象。

Slow motion animates sports, and sells iPhones,

慢动作镜头不仅能让体育赛事变得生动起来,还能提高手机的销量,

and is so powerful in movies it can make you forget everything else in the scene.

慢动作镜头在电影里的威力尤其强大,强大到能让你忘掉电影剩下的所有内容。

How does it work?

那它究竟是怎么做出来的呢?

To demonstrate the principles of slow motion,

为了演示慢动作的原理,

we actually hired a world-class juggler to show how a lot of the fundamental ideas —

我们还专门请了一位世界级的杂耍演员来展示基本的思路——

OK, you know, it throws me off when you pan up to my face, it's not supposed to be in the shot.

好吧,你拍到我的脸就等于把我给出卖了知道吧?镜头不应该框到我的脸的。

So...

所以……

Though this juggling is filmed with a digital camera,

虽然这个杂耍片段是用数码相机拍的,

the fundamental principles are the same as they were with film.

但用数码相机拍慢镜头的基本原则和用胶片拍是一样的。

This 1 second clip is shot and played at about 24 frames a second-24 pictures — today's standard speed for movies.

这一秒的剪辑无论是拍摄还是播放速度都是24帧/秒,这也是当下电影的标准速度。

Now let's say we film this at 60 pictures a second.

现在,假设我们以60帧/秒的速度拍摄。

If we play both clips back at a rate of 24 frames a second,

然后以24帧/秒的速度播放这两个片段,

the 60 pictures take 2 and a half times longer to play than just 24 pictures - that is slow motion.

60帧/秒的片段播放的时间就会比24帧/秒的片段长1.5倍——这就是慢动作。

This comes with some technical hurdles — especially when it comes to lighting.

这项技术也存在几个技术问题——尤其是亮度方面。

Imagine a door opening and closing to let light in.

想象一扇门在有光线照着的情况下开开关关。

If I take 24 pictures a second, the camera door - the shutter —

如果我以24帧/秒的速度进行拍摄,

will be open for about 1/50th of a second to let in the right amount of light for a nice amount of blur in the motion.

要想捕捉到适量的光线,同时保证照片模糊的程度也恰到好处,相机镜头——快门——就需要打开1/50秒左右。

Not enough blur, and things look disorientingly sharp.

左边(1/340秒快门)的片段模糊程度不够,图像看起来太过清晰。

Too much, and they look fuzzy.

右边(1/8秒快门)又模糊得太多了,看得人眼晕。

1/50th is just right for what we think of as a cinematic look.

在我们看来,快门速度设置成1/50秒的话放到电影里就刚好。

If I take 60 pictures a second, see how everything is darker?

如果我以60帧/秒的速度进行拍摄,看见没,整个画面都变暗了?

That's because I need to use a higher shutter speed when I'm shooting more frames per second —

这是因为我提高了拍摄速度就要使用更高的快门速度——

the door is slamming open and shut more quickly.

门开开关关的速度也就更快了。

There's less time for light to hit the camera's sensor (or the film).

光线照射到相机的传感器(或胶片)的时间也就更短了。

To lighten it, I have to crank the light or use more sensitive film (or in a digital camera, use a higher ISO setting).

要想让画面变得更亮,我就得手动调一下亮度或使用光敏性更强的胶片(又或者,是数码相机的话,就把ISO调高一点)。

But once all this is done, you can control not just how your picture looks — but how it moves.

不过,一旦做完这些准备工作,不仅图片的外观,还有图片的运动方式就都在你的掌握之下了。

Because these rules are so important to capturing any image,

因为这些规则对于捕捉任何图像都非常重要,

the potential to shape motion was obvious from the beginning of photography.

所以,从摄影诞生开始,慢动作拍摄塑造运动方式的潜力就一直非常明显。

And just like the slow mo tennis balls, early pioneers took lots of pictures quickly to slow down time—

和这个慢动作的网球杂耍一样,早期的摄影先驱们曾通过加快拍摄速度的方式来把时间变慢——

a process that transitioned to actually filming motion.

后来就逐渐过渡到了真正的电影拍摄。

See this crank?

看到这个摇杆了吗?

Early film was often - though not always - fed through the camera manually to control the speed of a picture.

早期的胶卷通常——虽然并不总是如此——都是手动送入相机的,为的是控制画面的速度。

Cameramen used this to their cinematic advantage.

摄影师们把这个办法搬到了电影拍摄上。

They often overcranked — cranked too fast — to put more film frames in front of the camera in a shorter period of time.

他们经常会摇过——摇得太快——为了在更短的时间内送入更多的胶片拍出更多的画面。

That would record slower motion.

那时候的慢动作就是这么拍出来的。

Or they undercranked — crank too slow — to make things look faster.

有时他们也会摇少——摇得太慢,让片段的节奏变快。

Movie projectors could be messed with too.

电影放映机的放映速度也能通过这种方式进行调整。

This 1897 film, Charity Ball, looks dreamy and slo mo when played at, say, 22 frames a second,

这部1897年的影片《慈善舞会》以,打个比方,22帧/秒的速度播放就会显得很梦幻,很慢动作,

but realistic when played at 40 frames a second.

以40帧/秒的速度播放就会很真实。

Setting rules for movies required the one thing that was missing. Sound.

要为电影定规则还需要一个我们前面没有谈到的因素:声音。

If I bounce this ball on a tennis racket, the speed of the audio and video have to be the same.

如果我用网球拍颠这个球,那我的音频和视频的节奏就必须一致。

Otherwise, it falls out of sync.

否则就不同步了。

This idea became increasingly important in the late 1920s,

到了20世纪20年代末,这一思路就变得越来越重要了,

when films with sound — called “talkies” — became the norm.

因为那时候,有声电影(talkies)已经常态化了。

They didn't work if film recording and playback speeds were all over the place — which they were.

如果电影录制和播放的速度乱成一团——确实有这种情况——就行不通了。

In 1927, the Society of Motion Picture Engineers noted that the sound recording device “must be perfectly synchronized with the camera.”

到了1927年,电影工程师协会指出,录音设备“必须与摄像机完全同步”。

The Jazz Singer, the first talkie, a 1927 movie that centered on a blackface performer,

第一部有声电影《爵士歌王》——1927年的一部黑脸滑稽戏——的一大功臣

was made thanks to a company called Vitaphone.

就是(华纳旗下的)“Vitaphone”工作室。

Their technology synced recording speed using a mechanical engine, not a person at a crank.

他们没有采用手动送入胶片的方式,而是采用了机械引擎来同步录制速度。

The Motion Picture Engineers followed Vitaphone's standard and settled on 24 frames a second.

后来,电影工程师们采纳了Vitaphone的标准,将电影的标准播放速度设定成了24帧/秒。

Confusion about playback and film speed was over.

关于回放和胶片进给速度的困惑终于画上了句号。

With a standard established, people were free to experiment.

有了标准,人们就可以自由地进行实验了。

Slow motion had already been used in science and sports,

当时,慢动作已经应用到了科学和体育视频领域,

like newsreel footage of baseball player Babe Ruth.

比如棒球运动员贝比·鲁斯的新闻短片。

Or in filmmaker (and Nazi propogandist) Leni Riefenstahl's Olympics documentary.

再比如电影制作人(兼纳粹宣传者)莱尼·里芬斯塔尔的奥运纪录片。

Beyond sports, there was some slow-mo dabbling in Hollywood,

除了体育影片,好莱坞也出了一些慢动作影片,

like the dreamlike hunting party photography in this 1932 musical.

比如1932年这部音乐片里这个梦幻的狩猎派对镜头。

In 1938, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers danced in slow-mo too.

1938年,(影史上著名的黄金搭档)弗雷德·阿斯泰尔和金杰·罗杰斯也(在《乐天派》中)跳起了慢舞。

But these slow motion scenes were rare.

不过,这些慢动作场景总体来看还是非常少见。

French Filmmaker and theorist Jean Epstein played with Slo mo in the Fall of the House of Usher.

法国电影制作人兼电影理论家让·爱泼斯坦也在《厄舍古屋的倒塌》中尝试了慢动作。

He wrote: “Slow motion really brings a new set of possibilities to dramaturgy.

他写道:“慢动作确实给戏剧构作带来了一系列新的可能性。

Its ability to dismantle feelings, to enhance drama...surpasses all the other known tragic modes.”

其消解情感、增强戏剧张力的能力超越了已知的所有悲剧模式。”

1930's French film Zero for Conduct featured a slow motion scene after a pillow fight — and it's like a Wes Anderson epilogue.

1930年的法国电影《操行零分》标志性的一幕就是枕头大战后的慢镜头——那一幕就仿佛韦斯·安德森的收场白一样。

Jean Cocteau's Orpheus used slow motion to add drama to a dreamy sequence.

让·科克托的《奥菲斯》里的慢动作则为梦幻般的顺序故事增添了一定的戏剧性。

Akira Kurosawa, whose groundbreaking hit Seven Samurai featured slow-mo,

慢动作也是黑泽明那部极具开创性的大片《七武士》的标志特色,

helped influence Hollywood to add slow-mo to action and narrative.

正是在他的影响下,好莱坞开始将慢动作拍摄融入到动作片和叙事里。

No longer just for sports, musicals, or outsider “artistes,”

慢动作镜头不再是体育片、音乐片和外围“艺人”作品的专属,

slow motion appeared at more than 100 frames a second in the final shooting in 1967's Bonnie and Clyde.

而成了1967年上映的 100+帧/秒的《雌雄大盗》定稿的拍摄手法。

By the ‘80s it was suitable for everything from blood rushing from an elevator to the end of a glorious race.

到了80年代,慢镜头已经适用于各种场景的拍摄,无论是电梯飙血的场景,还是一场辉煌的比赛的落幕。

Slow motion was an established trope by the 1990s - one with rules, and references, and expectations.

到20世纪90年代,慢动作已经成了一个既定的比喻,一个有着规则,参照,还有期望值的比喻。

“Ow!”

“啊!”

Even today, some tech obstacles exist.

即使是今天,慢动作拍摄也仍然存在一些技术障碍。

Film with your iPhone in regular motion and slow motion.

不信你可以拿起你的iPhone分别用常规速度和慢动作拍摄这个画面。

Notice that noise?

注意到那个噪音了吗?

That's the phone compensating for less light - by making the sensor more sensitive, raising the ISO.

那是手机在对微弱的光线进行补偿——通过提高传感器的灵敏度,提高ISO——的声音。

But for movies, with speeds at thousands of frames a second possible, and VFX augmentation common,

然而,拿电影来说,电影的拍摄速度有时可能达到上千帧/秒,还经常会用到VFX(视觉特效)技术,

slow motion has fully become an aesthetic storytelling tool rather than a technological hurdle.

慢动作拍摄已经彻底变成了一种电影讲述故事的美学手段,而不再是一个技术障碍。

It was obvious from the beginning of photography — but now slow motion has developed a full range of meanings and uses.

摄影初期慢动作的功能是比较显而易见的,但今天的慢动作已经有了更加丰富的含义和用途。

It can make 3:13 seconds iconic.

它能让一个3:13的片段成为一大标志。

A lobby run becomes a study in momentum.

让在大堂里的一次奔跑变成一次动量研究。

A bus stop becomes a reunion.

让公共汽车站变成一场重聚。

Reckless driving becomes flight.

把鲁莽驾驶变成飞车。

And bad juggling becomes a story of time and light.

还能把蹩脚的杂耍变成一段时间和光的故事。