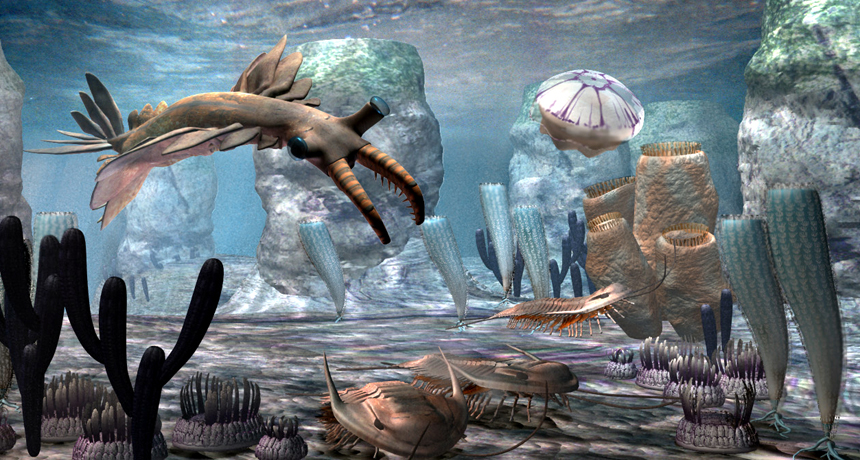

The Burgess creatures, they believed, weren't as strange and various as they appeared at first sight. "They were often no stranger than trilobites," Fortey says now. "It is just that we have had a century or so to get used to trilobites. Familiarity, you know, breeds familiarity." This wasn't, I should note, because of sloppiness or inattention. Interpreting the forms and relationships of ancient animals on the basis of often distorted and fragmentary evidence is clearly a tricky business. Edward O. Wilson has noted that if you took selected species of modern insects and presented them as Burgess-style fossils nobody would ever guess that they were all from the same phylum, so different are their body plans. Also instrumental in helping revisions were the discoveries of two further early Cambrian sites, one in Greenland and one in China, plus more scattered finds, which between them yielded many additional and often better specimens.

The upshot is that the Burgess fossils were found to be not so different after all. Hallucigenia, it turned out, had been reconstructed upside down. Its stilt-like legs were actually spikes along its back. Peytoia, the weird creature that looked like a pineapple slice, was found to be not a distinct creature but merely part of a larger animal called Anomalocaris.