How and when the Earth got its crust are questions that divide geologists into two broad camps—those who think it happened abruptly early in the Earth's history and those who think it happened gradually and rather later. Strength of feeling runs deep on such matters. Richard Armstrong of Yale proposed an early-burst theory in the 1960s, then spent the rest of his career fighting those who did not agree with him. He died of cancer in 1991, but shortly before his death he "lashed out at his critics in a polemic in an Australian earth science journal that charged them with perpetuating myths," according to a report inEarth magazine in 1998. "He died a bitter man," reported a colleague.

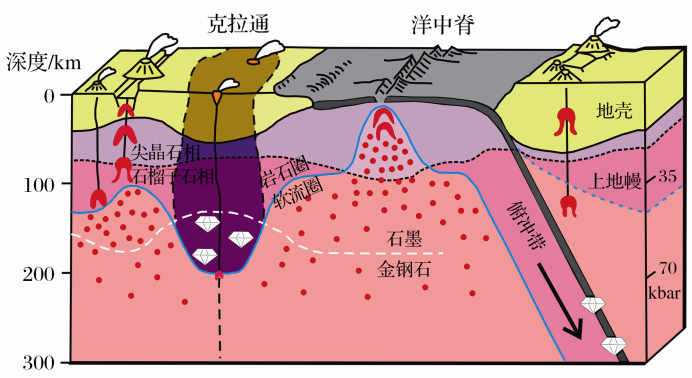

The crust and part of the outer mantle together are called the lithosphere (from the Greek lithos, meaning "stone"), which in turn floats on top of a layer of softer rock called the asthenosphere (from Greek words meaning "without strength"), but such terms are never entirely satisfactory. To say that the lithosphere floats on top of the asthenosphere suggests a degree of easy buoyancy that isn't quite right. Similarly it is misleading to think of the rocks as flowing in anything like the way we think of materials flowing on the surface. The rocks are viscous, but only in the same way that glass is. It may not look it, but all the glass on Earth is flowing downward under the relentless drag of gravity. Remove a pane of really old glass from the window of a European cathedral and it will be noticeably thicker at the bottom than at the top. That is the sort of "flow" we are talking about.