Taylor came from a wealthy family and had both the means and freedom from academic constraints to pursue unconventional lines of inquiry. He was one of those struck by the similarity in shape between the facing coastlines of Africa and South America, and from this observation he developed the idea that the continents had once slid around. He suggested—presciently as it turned out—that the crunching together of continents could have thrust up the world's mountain chains. He failed, however, to produce much in the way of evidence, and the theory was considered too crackpot to merit serious attention.

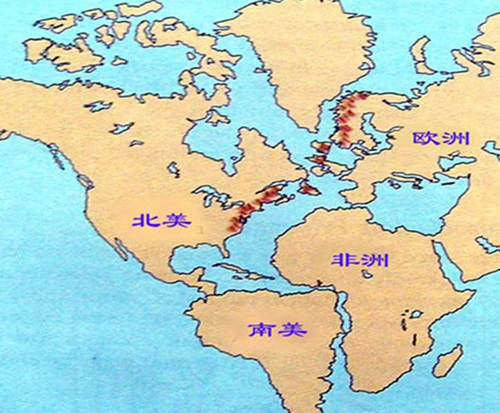

In Germany, however, Taylor's idea was picked up, and effectively appropriated, by a theorist named Alfred Wegener, a meteorologist at the University of Marburg. Wegener investigated the many plant and fossil anomalies that did not fit comfortably into the standard model of Earth history and realized that very little of it made sense if conventionally interpreted. Animal fossils repeatedly turned up on opposite sides of oceans that were clearly too wide to swim. How, he wondered, did marsupials travel from South America to Australia? How did identical snails turn up in Scandinavia and New England? And how, come to that, did one account for coal seams and other semi-tropical remnants in frigid spots like Spitsbergen, four hundred miles north of Norway, if they had not somehow migrated there from warmer climes?