But Egypt's foreign rulers, from the Romans to the Turks to the British, have always made free with Egypt's heritage.

埃及的异族统治者们,不管是罗马人、土耳其人还是英国人,都随意地处置埃及历史遗产。

Egypt, for two thousand years, had foreign rulers and in '52 much was made of the fact that Nasser was the first Egyptian ruler since the pharaohs, and I guess we've had two more since, although with varying results."

埃及已被异族统治了2千年,1952年,纳赛尔终于成为埃及自法老时代之后的第一位本土统治者。

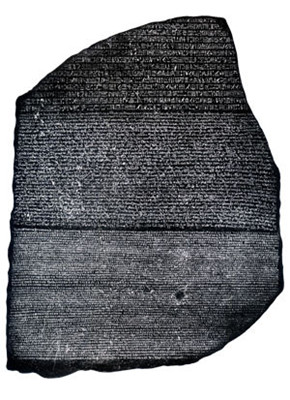

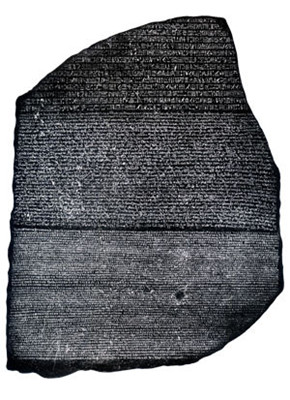

The Stone was brought back to the British Museum and immediately put on display-in the public domain, freely available for every scholar in the world to see-and copies and transcriptions were published worldwide.

石碑被带回大英博物馆后立刻进行了公开展览。全世界的学者都能参观,文字的抄本与拓本也一并公之于世。

European scholars now set about the task of understanding the mysterious hieroglyphic script.

欧洲学者立即着手破译神秘的象形文字。

The Greek inscription was the one that every scholar could read, and was therefore seen to be the key.

石碑上的希腊文每个学者都能读懂,这被认为是破译的关键。

But everybody was stuck. A brilliant English physicist and polymath, Thomas Young, correctly worked out that a group of hieroglyphs repeated several times on the Rosetta Stone wrote the sounds of a royal name-that of Ptolemy.

但没人取得任何进展。直到一位聪颖博学的英国学者托马斯杨发现一组在石碑上反复出现的象形文字代表了一个王室姓氏的发音—托勒密。

It was a crucial first step, but Young hadn't quite cracked the code.

这使得研究迈出了关键性的第一步,但他也没能成功破译所有文字。

A French scholar, Jean-Francois Champollion, then realised that not only the symbols for Ptolemy but all the hieroglyphs were both pictorial 'and' phonetic - they recorded the 'sound' of the Egyptian language.

法国学者让弗朗索瓦商博良其后发现,所有的象形文字都是既象形又表音的。这种文字也记录下了埃及语的发音。

For example - on the last line of the hieroglyphic text on the stone, three signs spell out the sounds of the word for 'stone slab' in Egyptian-'ahaj', and then a fourth sign gives a picture showing the stone as it would originally have looked:

例如,在石碑上象形文字的最后一行,先有三个符号代表了“石板”(埃及文为“ahaj”)一词的发音,紧接其后的第四个符号则描画了石碑原本的样子:

a square slab with a rounded top. So sound and picture work together.

一块有圆顶的方形石板。音与意便以这种方式结合起来。